Extension and Advisory Services should now support farmers by providing market information, organising inputs and provide other services to help them cope with restriction arising out of country- wide lockdown. But in the long run, the Ministry of Agriculture and the Department of Agricultural Extension should invest wisely to promote diversification that can potentially reduce financial vulnerabilities of small farmers and enhance more resilience to shocks similar to Covid-19, argues Dr Ranjan Roy

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) continues to wreak havoc in many countries. It has become one of the biggest threats to the global economy and financial markets. The World Bank says the COVID-19 pandemic might take a heavy toll on Asia’s economy; in the worst-case scenario, the region could face the sharpest downturn since 1997-1998 currency crises. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in its Interim Economic Outlook predicts the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on China and the rest of the world’s economy to be extremely severe. The UN warns that COVID-19 measures could cause a global food shortage.

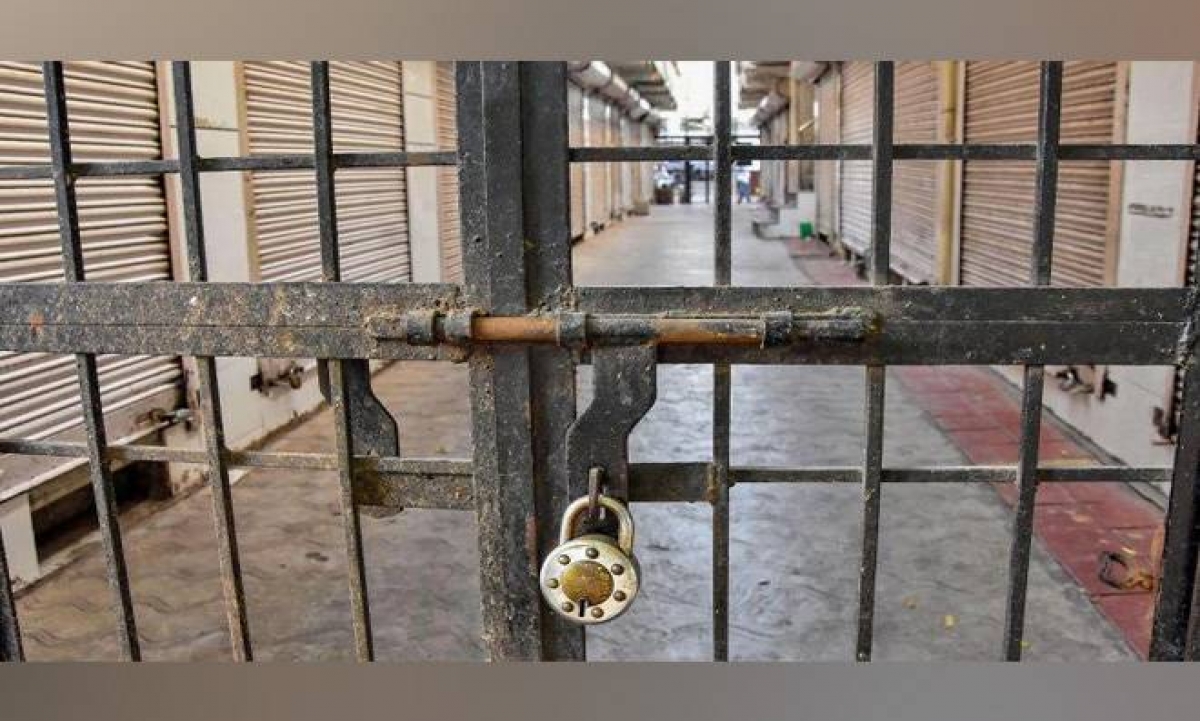

Nation-wide lockdowns are being imposed by several countries. This strategy puts in place a plethora of COVID-19 protecting measures (such as border closures, restrictions of movement, closure of restaurants, and community quarantines) resulting in restricted access to sufficient/diverse and nutritious sources of food. Restrictions significantly affect agricultural production, food supply and demand. Protectionist policies and a shortage of workers could see problems start within weeks, FAO shows.

COVID-19 IN BANGLADESH

On March 8, the Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research (IEDCR), reported the first COVID-19 case in the country. As on April 5, 2020, Bangladesh reported 88 confirmed cases of COVID-19. Among these, there have been nine deaths. In a bid to contain the spread of coronavirus, the government extended the ongoing shutdown until April 11. Agriculture products, fertiliser, insecticides, foods, goods, medical equipment, daily essentials, kitchen markets, restaurants, drug stores, and hospitals remain out of the purview of the shutdown. Public transportation and banking services are limited. Bangladesh Bank, the country’s central bank, issued necessary directives to keep banks open on a limited scale during the shutdown.

The government of Bangladesh has advised everyone to stay home during this period. The army has taken stern actions from April 2 against violations of the government’s directive on maintaining social distancing and home-quarantine. It is being reported that people in many places are not complying with the directives. There is movement, mainly for securing livelihoods. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has been directing authorities to provide food aid to daily wage earners. The Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief reports that food support is being provided to farm laborers and other beneficiaries. The government of Bangladesh announced Tk. 5,000 crore ($5.9 million) stimulus package to help export-oriented industries to counter the economic impact of COVID-19.

IMPACT ON AGRICULTURE

The COVID-19 impact on agriculture is substantial, although it is still unfolding. Initially, the country’s fish and dairy producers bore its brunt. For instance, farmers involved with crab, shrimp, and fish production face several export bans resulting in significant economic loss. Bangladesh’s exports make up more than 70 percent of the crabs in the Chinese market. An export ban in China means a significant loss for the Bangladeshi crab industry.

There are unofficial estimates that the current market price of milk is down 40% compared to January’s price. COVID-19 could have a catastrophic impact on the dairy sector in the country, according to a leading industry group. Prices for vegetables, paddy, cattle and other farm goods are also falling. Small-scale farmers are vulnerable to the impacts of COVID-19 as they might be hindered from working on their land or accessing markets to sell their produce, buy seeds and other inputs. A leading think tank mentions that the pandemic is adversely impacting segments of agriculture as the demand for food has dramatically increased, while orders and events are getting canceled.

As of now, disruptions are minimal as food supply has been adequate and markets have been stable. Experts opine that close of transport routes, restrictions and quarantine measures, shortage of labor and spikes in product prices are obstructive for fresh food supply chains and might also result in increased levels of food loss and waste. The people in Bangladesh are wasting about 5.5% of the total procured food, a study says. These obstructions are likely to impede farmers’ access to markets, curbing their productive capacities and hindering them from selling their produce. Shortage of labor could disrupt the production and processing of food, notably for labor-intensive crops.

Panic related to food and agriculture is an additional concern. Panic-buying disrupts food distribution. As COVID-19 spreads, staples are stockpiled, leaving markets empty. Evidence indicates that quarantines and panic-buying during the Ebola Virus Disease outbreak in Sierra Leone (2014-2016), for example, led to a spike in hunger and malnutrition.

COVID-19 could affect food demand in various ways. Usually, when reduced income and uncertainty make people spend less and result in shrinking demand the sales decline. So does production. In the period of lockdown, people visit food markets less often, affecting their food choices (buying more cereal crops) and consumption, i.e., a rise in eating at home. Food demand is linked to income. Hence, poor people’s loss of earnings could impact consumption.

Agricultural production and trade are likely affected by many policy measures (e.g., implementing higher controls on cargo vessels) aimed at avoiding further spread of COVID-19. Production could be hampered due to restrictions of free movement of people as well as a shortage of seasonal workers. These barriers ultimately affect market prices.

Agricultural trade restrictions hinder trade and mobility of commodities, including food, feed, and input supplies. Suspending nation-wide transportation might affect agricultural and food trade. The slowdown in fertilizer, fuel and other input movement, and their reduced availability, is already a growing concern for the upcoming season. Studies show that trade barriers will create extreme volatility. The UN’s food body warns, “Protectionist measures by national governments during the coronavirus crisis could provoke food shortages around the world.”

RESPONDING TO COVID-19 IMPACT ON AGRICULTURE

The coronavirus pandemic is causing significant economic slowdowns (when economic activity is growing at a slower pace) and downturns (when there is no growth, but only a period of decline in economic activity), which are associated with rising hunger levels as FAO reports. Bangladesh government must adopt useful measures to mitigate the food and agriculture crisis.

First, meeting the immediate demand (e.g., food needs) of profoundly affected people. Emergency food needs can be ensured by distributing food to the most vulnerable families and improving communication about access points for food deliveries, distribution times and measures to reduce the risks. The Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE) and allied organisations must take initiatives like observation and monitoring for smooth agricultural production by providing market information, inputs and other services. The DAE, NGOs and private organisations (input dealers) have to play a crucial role in promoting public health—the science and art of preventing disease. Lessons have to be taught about biosecurity measures such as hand washing, wearing masks, staying home if sick and maintaining social distancing.

Second, boosting social protection programs to protect incomes and purchasing power. The government has already introduced some protective measures to combat the impacts of the pandemic on people’s livelihoods. The agricultural extension and advisory services might advocate for conditional or unconditional cash transfers, public works programmes that help reduce unemployment or policies aimed at stabilizing food prices, and protecting incomes from damaging out-of-pocket healthcare costs by ensuring coverage of essential health services. Using the DAE and NGOs networks, the central bank could inject funds in the agricultural sector through a grant facility, which might help agro-based micro, small & medium enterprises (SMEs), casual laborers and salaried staffs.

Third, relief from trade restrictions to keep food, feed and input supplies. Active measures (such as providing subsidies for food consumers and reducing import tariffs) are required. The government could temporarily reduce VAT and other taxes, review taxation policy to imported goods to compensate for potential cost increases, and assess exchange devaluation’s potential impacts. The DAE says we essentially need monitoring and care to avoid accidentally tightening food-supply conditions. In this regard, extension personnel and digital technologies have a role to play in anticipating problems and managing temporary shortages.

And fourth, resolving logistics bottlenecks and efforts to slow the spread of the virus. The government requires stimulus and safety-net measures (like health screening before leaving the factory) to reduce impacts on farm product delivery, pickup workers and processors. The Ministry of Agriculture (MoA), DAE and Bangladesh Agricultural Development Corporation (BADC) must implement measures for mitigating impacts incurred by the slowdown in agricultural inputs movement and availability.

WHAT MORE NEEDS TO BE DONE AND HOW?

As a global crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic demands a coordinated response. The DAE, as a flagship organisation in Bangladesh engaged in agricultural policy development and technology dissemination can perform other major roles to mitigate COVID-19 impacts on food and agriculture. These include:

Conducting participatory COVID-19 impact assessments to map the pandemic’s effects on people’s food security and livelihoods, derive proactive measures and to determine what assistance the Bangladesh government requires from development partners such as FAO, IFAD etc.

Highlighting critical gaps in (district/regional) agricultural emergency preparedness. Developing (district/regional) an agricultural contingency plan would be vital to take action when faced with upcoming economic slowdowns and downturns in a timely and effective way.

Diversifying and enhancing agricultural production to combat the current and imminent crises in this country as well as to contribute to achieving global food security.

Building resilient agriculture is essential. Lack of comprehensive agricultural planning and preparation for the outbreak has starkly demonstrated the importance of resilience—the ability for human systems to anticipate, cope and adapt.

Inculcating lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic – this pandemic is a stark warning of what can happen when we fail to prepare for climate crisis. In the context of prevailing climate emergency, the impacts of COVID-19 reteach us that an ounce of prevention (e.g. initiatives for reducing GHGs) is worth a pound of cure, i.e. avoiding climate catastrophe.

CONCLUSIONS

The COVID-19 challenge seems unprecedented, but the governments and its agencies, in particular the agricultural extension services, can and should adopt proactive measures both to contain the spread of the disease and to safeguard the economy. In the short term, the DAE and other organisations must meet the farming community’s demands, support them in increasing their income, ease food-supply conditions and take other measures to counteract economic adversity. In the longer term, the Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) and the DAE have to invest wisely to diversify the agrarian economy from commodity dependence, which reduces financial vulnerabilities and builds capacity to withstand and recover following economic turmoil.

Dr Ranjan Roy is an Associate Professor in the Department of Agricultural Extension and Information System, Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, Dhaka-1207. Bangladesh. Email: ranjansau@yahoo.com